The White Ribbon (2009) is something of a landmark film within the filmography of Austrian master Michael Haneke. For one, it is the only one of Haneke’s feature films to be a period piece — a rare historical outing for a director who typically delves into the dark side of contemporary life. For another, it’s his first film to win the coveted Palme d’Or, an incredible achievement he would replicate with 2012’s Amour.

The White Ribbon tells the story of a small village in northern Germany between 1913 and 1914, where a series of strange incidents begins to occur. The village doctor is injured after his horse trips on a wire mysteriously stretched between two trees, someone destroys the cabbage field, and a young boy goes missing. These events are narrated to us by an old man, who we see in flashback as a schoolteacher in his 30s (Christian Friedel), and who begins to investigate the occurrences himself.

That may suggest an overarching whodunnit premise, but this is no Agatha Christie-style caper. The White Ribbon is one of Haneke’s most ambiguous works, and like most of his films, it gives the audience space to interpret its meaning for themselves. What is clear is that Haneke’s primary concern here is the relationship between adults and children — and the implications of that power dynamic.

The title itself refers to a form of punishment the pastor imposes on his children: tying a white ribbon around their arms to remind them of the innocence they must strive for. It is this element in particular that has led critics to theorize that the film is about the origins of Nazism — that the cruelty of authoritarian adults leads to violence on a grander scale.

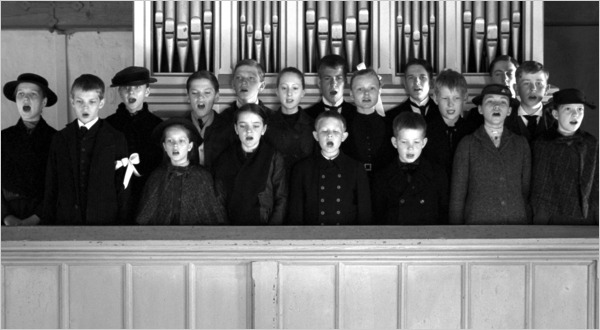

All this is, of course, open to interpretation, and while the theory is intriguing, there isn’t a great deal of direct evidence to support it. What is undeniable, however, is the film’s visual beauty. Gorgeously shot on film and graded in post to black and white, Haneke and cinematographer Christian Berger achieve a timeless look, as though we’re watching a long-lost Ingmar Bergman classic. Haneke’s terrific instinct for casting also pays off. Each face on screen seems to have stepped straight out of the past. The child actors are particularly impressive, the pain behind their eyes hinting at the guilt and shame inflicted upon them by their guardians.

The White Ribbon is perhaps too glacial in its pacing, and a snappier edit might have made the story feel sharper — but it is nevertheless Haneke at his most uncompromising and enigmatic. A modern classic that truly deserved its accolades.