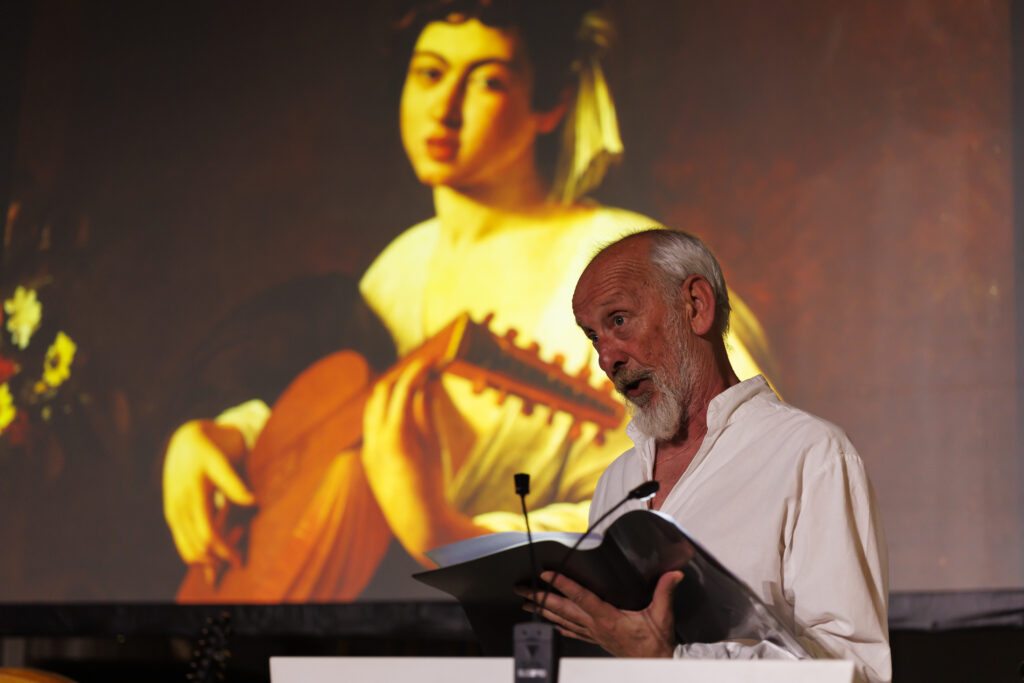

‘MUSIC BY CARAVAGGIO’, proclaimed narrator Stephen Oliver with actorly gravitas, his voice filling the length of the Cardinal’s Hall. Wait, what? Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610), celebrated painter of the Italian Baroque and not the least of Malta’s tourist attractions, also composed music?! Well, not literally. With these words the curtain was lifted on an innovatively curated concert advertised under the title ‘Music Painted by Caravaggio’. I don’t know whether this elision of the word ‘painted’ was deliberate, but the jarring metaphorical slippage somehow made the point: Caravaggio was the author of this concert programme.

The idea was apparently inspired by four Caravaggio artworks that depict musical text, usually in the form of partbooks, with sufficient detail that the piece in each case has been (with one exception) accurately identified by musicologists. In this concert performance, held in the Inquisitor’s Palace, Birgu, and part of the Malta International Arts Festival 2025, the four paintings and the music represented in them form the basis of a larger concert programme dedicated to Italian-language madrigals for small vocal ensemble (members of Malta’s national choir KorMalta directed by Riccardo Bianchi) and with lute accompaniment expertly provided by Renato Cadel.

The four paintings – namely Rest on the Flight into Egypt, The Lute Player, The Musicians and Amor Vincit Omnia – made up the four main sections of the evening, each one introduced by the narrator (Oliver) with images of the artworks projected onto a screen just behind the performance area, so that each section began with an engaging, informative illustrated lecture. This was followed, in each case, by a series of three or four pieces including the one depicted in the artwork. In fact, the relationship between artwork and musical programme is not quite as close as it seemed initially. As the narrator pointed out, the programme featured only two of the madrigals depicted in the four artworks (Rest on the Flight into Egypt and The Musicians): the partbook shown in The Lute Player is from ‘Voi sapete ch’io v’amo’ by the Franco-Flemish composer Jacques Arcadelt, whereas another madrigal by the same composer (‘Chi potrà dir quanta dolcezza provo’) was performed instead; and the musical notation depicted in Amor Vincit Omnia so far remains unidentified, so the repertoire in this final section was less a specific reference to the painting than a wide embrace of the Virgilian expression (‘Love conquers all; let us, too, yield to love!’).

Despite the gimmick potential, the collaborative, multimedia element of the programme was imaginative and elegantly realised, especially the incorporation of the artwork into the whole experience. There is a witty symmetry in the concept too: the 16th-century madrigal is a musical setting of a secular poetic text that brings the events and affects of the text vividly to life through techniques of musical mimesis and imitation. Whence the term ‘madrigalism’, otherwise known as ‘word-painting’. Just as a madrigal ‘paints’ the words of the lyrical text that it sets, the Caravaggio artworks chosen for this concert themselves depict madrigals as musical text and as a tangible, material object. The narrator didn’t comment specifically on the symbolic function of the artist’s choice of these particular madrigals in the wider context of the artwork. Perhaps it didn’t matter; the point was to use the artwork as a point of departure for an attractive selection of 16th- and 17th-century secular musical repertoire.

Musically speaking, this concert represented an international collaboration between a local ensemble (KorMalta) and visiting artist Cadel, whose lute accompaniment in the madrigals provided a graceful, reassuring stage presence that held the ensemble together with discretely minimal outward gesture. Meanwhile, the lute solos (a Toccata by Kapsberger and Palestrina’s ‘Vestiva i colli’ from the Raimondo Manuscript) added a more intimate, improvisatory flavour to the evening. Further highlights of the programme were the madrigal ‘Ben può di sua ruina’ by Pompeo Stabile, the very piece that appears in Caravaggio’s The Musicians: there were effective moments in the ensemble singing and in Bianchi’s direction, especially the ending when the lute drops out and the voices find a lovely pianissimo dynamic, almost disappearing behind the hum of the air conditioning. And the performance of the final number, ‘Amor vittorioso’ by Gastoldi (inexplicably rechristened ‘Amor Vincitore’), had a liveliness to it and a unity of purpose that closed the evening in good spirits.

In general, however, and despite some appealing soloistic turns, the vocal performance was marred by insecure ensemble, wobbly intonation and interpretative inconsistency. Indeed, there were several moments in the programme where the ensemble fell apart and only just came together for the final chord. Additionally, the consort of six singers, including director Bianchi who provided a voice part in at least one of the items, represented such a wide range of voice types that coherence of tone quality was only rarely achieved. As for the rhetorical aspect of these madrigals, there was clearly some effort to bring the poetry and music to life in performance. But these moments came across as isolated and eccentric rather than as part of a larger, informed vision of this specialist repertoire. The narrator quoted briefly from some of the poetic texts in the introductions, but for the meanings to really carry to the audience in performance, a copy of the texts and a translation either on the screen or in a physical programme would have been beneficial.

As for the selection of repertoire, this concert presented madrigals many of which are only rarely heard today. It is a shame that madrigals by women composers were not also featured. Even within the somewhat narrow definitions of the chosen repertoire (predominantly 16th-century madrigals), there are several composers, such as Maddalena Casulana and Vittoria Aleotti, who made important contributions to the genre and whose work would have considerably enriched the programme.

In the end, what promised to be an intriguing dialogue between artforms was sadly compromised by the overall musical performance. Love Conquers All, perhaps; but sometimes love alone is not quite enough.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Music Painted by Caravaggio

Inquisitor’s Palace, Birgu

20th June 2025

Choir Director – Riccardo Bianchi

Lutenist – Rentato Cadel

Choir – KorMalta: Alexandra Camilleri Gambin, Bianca Simone, Peter Wagstaff, Jester Rosales, Albert Buttigieg

Narrator – Stephen Oliver