Charlotte nearly didn’t go, but with Kritikarti’s encouragement, Charlotte now believes that she would’ve missed a masterclass in local musical theatre craftsmanship. This is a review following an intensive one-and-a-half-hour post-performance discussion, with editorial comments.

Charlotte: black

Mireille: red

Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Into the Woods intertwines the plots of several Brothers Grimm fairy tales, pulling them into a single narrative that asks: what happens after “happily ever after?” A production that leans into the whimsy and highlights the moral ambiguity. That’s no easy task. Teatru Manoel’s latest production, directed by Lucienne Camilleri, is one of the most technically complex musicals I’ve seen staged locally.

Indeed, from our discussion last Sunday, we came to appreciate Sondheim’s ability to bring forward the human element to fairytales and their fantastical nature. This production, with a highly attractive cast and production design, showcases Maltese talent to a tee. Overall, an entertaining experience.

What stood out just as much as the technical and artistic achievement was the strong sense of community behind it all. It was inspiring to see so many creative minds come together with one clear, unified goal.

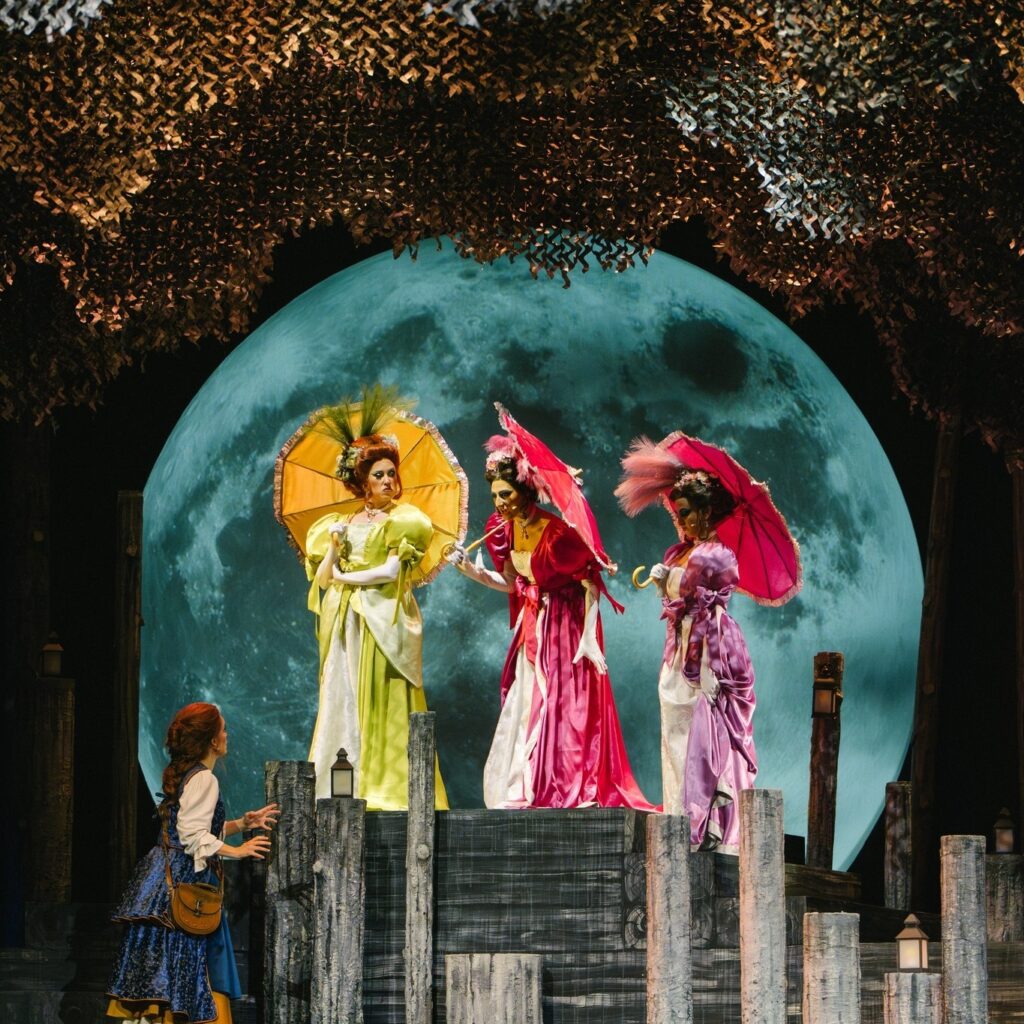

I have to acknowledge the world created here. Production design by Matthew Cassar was a standout: a greyscale, pop-up storybook forest. It was dense, layered, and it worked. The physical set is made up of staircases, narrow platforms, and limited space to roam. With big gowns and heels, navigating the space must have been a challenge, yet the cast moved through it with impressive ease.

The storybook concept tied well with the overall fairytale thematics and complemented Teatru Manoel’s architecture. Yet, this is where I felt that, while the pop-up fairytale style was once again cleverly employed, the density of the design required more space than the Manoel stage could provide. Given that this musical demands fast-paced action and swift transitions between scenes, the performers’ movements at times felt constrained and occasionally awkward. There were moments where their entrances and exits appeared unnatural, executed simply because the script required them, without clear motivation. As a result, some movements felt out of place or lacked coherence.

The lighting design played a crucial role in bringing this world to life, using the grayscale backdrop to seamlessly shift tones and emotions. It allowed for subtle adjustments in mood, sometimes highlighting the vibrancy of a moment, other times leaving the stage muted and introspective. The lighting was well thought out – so delicate, with ethereal lighting trickling down between the tree canopy, giving into the dense forest.

The costume design further supported the actors, with each piece thoughtfully crafted to help them fully embody their roles. The intricate detail of the costumes not only added to the aesthetic but enhanced the performers’ physicality, allowing them to inhabit their characters more deeply. The costumes aided the performers in their characterisation, however, I am unsure whether such costumes complemented the set and mood, making me reminisce about Maltese panto, rather than the dark reality of a Grimm Fairytale. Hair and makeup, too, were meticulously crafted, with each choice contributing to the visual storytelling, further defining the personalities of the characters. A great example is Rapunzel’s long, plaited wig, meticulously woven and decorated. The combination of these design elements truly elevated the overall production.

Sound-wise, this show is a beast. Sondheim’s score is notoriously difficult, no musical breath wasted, every phrase loaded with intention. Musical Director Ryan Paul Abela and the orchestra tackled it with technical finesse. From the opening prologue, the energy was high and consistent. Diction was clear and deliberate, a testament to the cast’s classical training and the musical director’s attention to detail. At times, when the Narrator and the full company came together, the sound teetered on overwhelming. I found that we were overwhelmed by the intensity of the voices and music, losing the very needed clarity. It made me wonder: what would this have felt like unmic’d? The Manoel has great natural acoustics, and this cast, built of vocal powerhouses with classical training, could probably handle that. A missed mic cue proved this; Talitha Dimech, the Stepmother, projected with clarity over a mic’d orchestra to the back of the theatre, where we were sitting.

Performance-wise, there’s a lot to unpack.

Joel Parnis, as the Baker, gave a strong vocal performance, but at times, his portrayal veered more into caricature than staying grounded in the character’s moral struggle. As one of the more ‘realistic’ characters in the show alongside the Baker’s Wife, I would have liked to see more depth in his portrayal, particularly in the first act, where his emotional complexity seemed overshadowed by exaggerated delivery. Rachel Fabri as the Baker’s Wife was technically precise, with a voice that fit Sondheim’s score well. She managed to balance caricature with staying grounded in the character’s moral struggle, though this sometimes clashed with Parnis’s portrayal. To add on to this reaction, having such ‘original’ characters outside of the fairytale ones required a more grounded and complex approach, rather than the caricature-style acting.

While their duet, ‘It Takes Two,’ was clear and musical, the chemistry between them didn’t fully land. While relationships naturally have their ups and downs, ‘It Takes Two’ serves as a crucial moment of realisation for both characters. However, it didn’t quite deliver the emotional weight it required. This left me curious about the directorial choices behind their portrayal. Thus, if this was a directorial decision, the ‘ups and downs’ of a relationship and teamwork did not land. Parnis had a charm and action-figure-like stiffness that oddly reminded me more of one of the Princes, which was portrayed well by Thomas Camilleri’s Cinderella’s Prince. I’d be curious to see him in that role. By contrast, Ryan Grech’s portrayal of Rapunzel’s Prince felt more in line with what one might expect from a morally grounded interpretation of a different character, such as the Baker. Still, by the final scene, when the Baker stood beside Cinderella, Jack, and Little Red, there was a quiet cohesion that settled in.

Nadia Vella gave a textured performance as Cinderella. Vella’s Cinderella matured visibly between acts; by the second, she was no longer running away but making active, often difficult choices. Her portrayal was one of the most balanced in the cast, grasping the fantastical while holding tightly to the moral core of the piece. Her portrayal was true to the necessity of Sondheim’s moral ambiguity in this musical.

Christina Despott’s Little Red Riding Hood was sharp, fiery. Her delivery had bite, and she played the comedy well. Still, I did find myself questioning the casting choice, not because of talent, but because the role traditionally skews younger. The contrast in age between her and Gianluca Cilia’s Jack occasionally disrupted the sense of childlike wonder the two characters share. That said, Cilia brought a tender vulnerability to Jack. He captured Jack’s growth from boyish naïveté to the weight of consequence. I hope he leans into the role more as performances continue.

Dorothy Bezzina was captivating as the Witch. Her performance brought nuance and complexity to a character that teeters between caricature and profound tragedy. Bezzina navigated the shift from villain to mother with sensitivity, never losing the character’s otherworldly edge. It was a layered, emotionally intelligent performance that anchored the production in many ways. A whirlwind of stamina and a masterclass in musical performance-making, Bezzina made the musical an enchanting experience for all.

Special credit must go to the movement artists, Nicole Arrigo, Tess Attrill, Keith Dimech, Dean Ellul and Nina Galea, who brought the production’s puppetry to life. Created by Theatre Anon, Milky White, the birds, and the Giant were handled with precision and care. The puppetry never felt like an add-on; it was fully integrated into the storytelling, enhancing the world without pulling focus. The Giant’s shadow, the scale, and coordination required to bring it to life should not be overlooked, and in this production, it worked.

The first act is self-contained and ends tidily, whereas the second act is where things unravel. It demands more of one’s emotional attention. There were audience members who left after Act I, likely a reaction to the above rather than the quality of performance per se. While the musical closes the first Act with all the tasks completed by the leading Couple, the looming ‘Chekhov’s Gun’, or Giant, mentioned time and time again through small quips by Jack or his mother, was lost on the audience. This is where I believe that audiences left during the interval due to misunderstandings, uninformed expectations, or general ignorance of the musical and the reality of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Such a reaction as leaving at the end of the first Act is a potential reflection of the Americanisation of these fairy tales, where the Disneyfication has thwarted their moral lessons into happily-ever-after.

I’ve often said I could have walked away from this musical satisfied after Act One, but this time, I’m glad I got the chance to experience it again and gain further insight. Something clicked, and I finally understood why Act Two exists. Into the Woods is meant to overwhelm you. These are fairy tales colliding, dreams collapsing, intentions clashing. Into the Woods is a production that draws you in with magic, only to leave you reflecting on grief, accountability, and the complexities of adulthood. I was hesitant about going to this musical, though I’m happy Kritikarti encouraged me to go. Showing up with curiosity and sitting in discomfort is not so bad afterall. You might be surprised!

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

| Baker | Joel Parnis |

| Baker’s Wife | Rachel Fabri |

| Witch | Dorothy Bezzina |

| Cinderella | Nadia Vella |

| Narrator/Mysterious Man | Stephen Oliver |

| Jack | Gianluca Cilia |

| Little Red Riding Hood | Christina Despott |

| Jack’s Mother/Cinderella’s Mother | Stefania Grech Vella |

| Cinderella’s Prince | Thomas Camilleri |

| Rapunzel’s Prince | Ryan Grech |

| Rapunzel | Bettina Zammit |

| Cinderella’s Stepmother | Talitha Dimech |

| Lucinda | Bettina Mattocks |

| Florinda | Rebecca Darmanin |

| Wolf | Karl Bartolo |

| Steward | David Ellul |

| Grandmother | Nicole Arrigo |

| Cinderella’s Father | Noel Zarb |

| Movement Artists | Tess Attrill, Keith Dimech, Dean Ellul and Nina Galea |

| Director | Lucienne Camilleri |

| Musical Director | Ryan Paul Abela |

| Production Design | Matthew Cassar |

Source: TeatruManoel.mt