Pelopida: A Revival Not Yet Fully Alive

The crowning event of this year’s edition of the Valletta Baroque Festival was an ambitious undertaking in the revival of early Maltese music: a production of the recently rediscovered opera Pelopida by the Maltese Baroque composer Girolamo Abos. As the festival’s artistic director and the project’s chief instigator Kenneth Zammit Tabona has noted, the venture has been in development since before the pandemic. This year, the opera was finally staged in its entirety for the first time in living memory, nearly three centuries after its premiere in 1747.

The libretto by Roman poet Gaetano Roccaforte revisits the tale of Theban statesman Pelopidas through the moral machinery of opera seria: honour, loyalty, love—virtues that, here as elsewhere, spend much of the evening being sworn, tested, and re-sworn. Abos, like many Maltese composers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, travelled to Naples at an early age to pursue his musical education in one of the city’s prestigious conservatoires, studying under Gaetano Greco and Francesco Durante. Pelopida is therefore distinctly Neapolitan in style—an opera seria in number form that dutifully observes the genre’s conventions.

The project deserves real praise for its archaeological value and broader cultural ambition. Yet the production itself was not without its shortcomings.

Let us begin with the good news: vocally, the cast proved the production’s principal strength. In the title role, the Italian tenor Valentino Buzza brought a charismatic stage presence and a robust, generously projected instrument. The voice’s natural weight—impressive in declamatory passages and cantabile—was less advantageous in Abos’s more virtuoso writing. In the rapid passaggi di coloratura, articulation could sound slightly laboured, with a degree of heaviness affecting rhythmic definition and the sense of buoyant line that the Neapolitan style ideally demands.

As Aspasia, Lorrie Garcia offered a rich, warmly coloured timbre to the character. In the lowest tessitura, however, the tone sometimes thinned and became air-led, losing definition and suggesting a degree of register-management strain. This is a familiar casting reality: true contraltos are comparatively rare, and such roles are frequently entrusted to mezzo-sopranos with a strong, well developed lower register. I suspect Garcia’s vocal profile belongs to this category.

Countertenor Filippo Mineccia, as Egisto, and Lucija Varšič, in the trouser role of the young Oreste, both delivered solid, dependable performances.

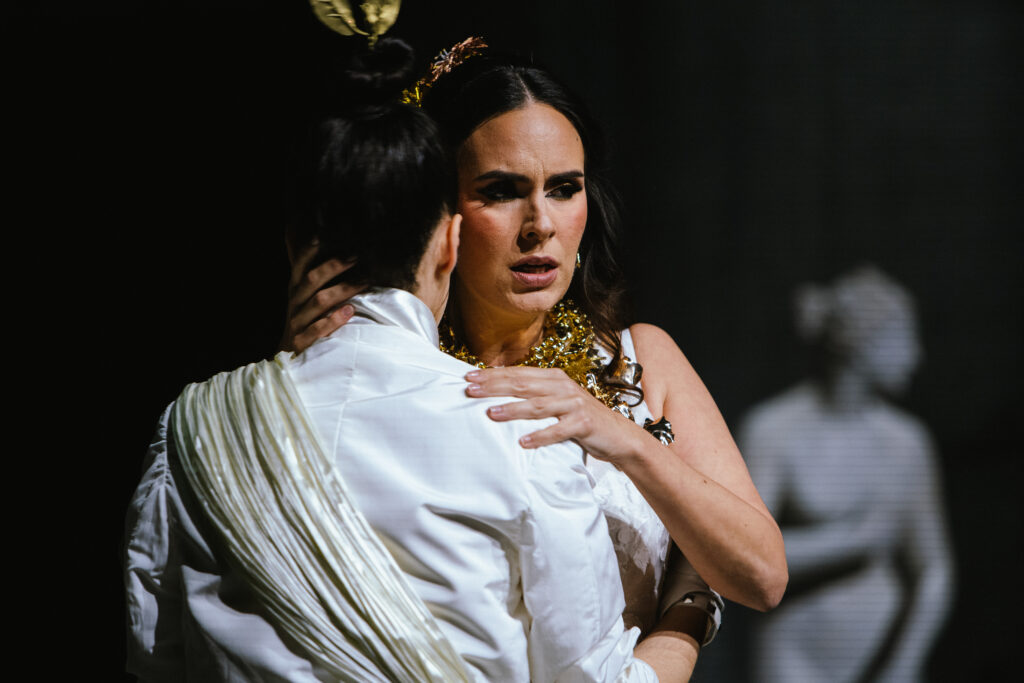

But the evening’s indisputable show-stealer—judging by the curtain-call ovation—was the Italian soprano Vittoriana De Amicis, cast as Clito in a fearsomely virtuosic second trouser role. Her performance combined exceptional agility with stamina: in extended, high-lying writing such as ‘Sento che a suo talento già mi trasporta’, and again in the cavatina and aria ‘Trapassami il petto… Ah, mi si arresta il sangue’, she sustained the demands of rapid passaggi di coloratura—runs, trills, and fioriture—without any appreciable loss of projection or dramatic voltage, her voice retaining both size and point (that all-important squillo) even at the end of a long evening. De Amicis has refined her technique with bel canto specialists Mariella Devia and Antonella D’Amico, and the pedigree shows in the clarity of her line and in her clean, purposeful articulation.

Another welcome discovery was the young soprano Carlotta Colombo as Ismene. She distinguished herself through the purity of her timbre, an effortless grace, and a finely controlled filato—that spun, threadlike tone that lends the vocal line a kind of filigree delicacy. If her recent European tour with Joyce DiDonato and Il Pomo d’Oro is any indication, she is a singer to watch—and one hopes this is only the beginning of a bright career.

I regret to report that the Arianna Art Ensemble, under the direction of the Italian conductor Giulio Prandi, did not consistently meet the cast’s level. Although the performance was overall effective in outline, it was undermined by recurring moments of ensemble insecurity and lapses of intonation, beyond the usual margin of roughness associated with period instruments. A notable exception came from the continuo work: harpsichordist Daniel Perer and theorbo player Giulio Falzone were superb throughout, materially raising the musical standard whenever they were in play.

The staging—direction, design, and costumes—left me unconvinced. Stage Director Brett Nicholas Brown’s stated aim was to ‘transform ancient Thebes into a sculpture museum,’ and Anthony Bonnici’s set delivered exactly that: an installation of faux-marble statues, occasionally draped, literal in conception and uncertain in overall effect. Brown’s contemporising touches—a security alarm sounding, a wedding ‘family photo’ snapped on a digital camera—read as deliberate anachronistic winks, lightly puncturing the solemnity of the drama.

My main objection is an aesthetic one. The pairing of marble statuary and Luke Azzopardi’s predominantly white, high-sheen satin costumes produced an aggressively bright, reflective palette: sleek, plastic-looking, and edging towards kitsch without quite committing to camp. One can concede that taste is subjective, but the show’s overall aesthetic was, frankly, hard on the eye.

I had my reservations about the dramaturgy, too. The acting style remained in a permanently heightened register; among fistfights, swordplay, emphatic gesturing, declamatory monologues, love triangles and quadrangles, the result was paradoxically flat. With intensity treated as the default setting, the drama lacked contour: little modulation, little contrast, and therefore few genuinely climactic moments. A measure of restraint at key points would have allowed the emotional peaks to register, rather than simply accumulate. Opera seria in number form is already predisposed to stasis: long stretches of rhetorical exposition, arias in suspended time, and dramatic movement carried more by affect than by action; a staging that keeps the temperature permanently at full boil only amplifies the genre’s inherent flatness, rather than supplying the contrast and pacing that is required to prevent modern audiences, as one Robert Schumann once ruthlessly remarked, from indulging in self-meditation (i.e. falling asleep.)

In the end, Pelopida as a revival project—and as a statement of intent for Maltese Baroque music on a major festival stage—was easier to admire than its overall execution. A strong cast did much of the heavy lifting, only to be undermined by instrumental shortcomings and a less-than-flattering production, amounting to a sense of wasted potential. A valuable resurrection, then—just not yet the fully living creature.